Dave Greber’s "HomeOffices" Exhibition at Public Access Memories

screen-cap of actual gameplay x2 speed

A Virtual Remote Work Culture Exposition

HomeOffices

Dave Greber Solo Exhibit

@PublicAccessMemories.com

launched July 27, 2024

18 interactive, evolving pages

w/ pop-up videos and easter eggs

Credits:

Programmer: Jenna deBoisblanc @jdeboi

Essay: Emily Farranto @thevillagedisco

Technician: Nathaniel Britton @natejbritto

Printer: Paper Machine @antenna.works

The Call From Inside the Home Office: Dave Greber’s HomeOffices at Public Access Memories

The 2020 pandemic lockdown left its mark on our collective psyche and changed the shape of certain corners of our lives. While many were suddenly out of work, others were forced to merge work and home lives, blurring temporal and spatial boundaries, turning tables into desks and small rooms into offices. When the lockdown ended, many jobs continued on a work-from- home or hybrid structure. Even those whose work lives were not directly upended by the pandemic, the employer assumption that workers are available outside work hours has been normalized. There is no consensus about whether the shift toward a work-from-home economy has done more harm than good for individuals and families. Dave Greber’s exhibition of interactive digital collages, HomeOffices, suggests there is something grotesque about this grafting of work and home, grotesque but laced with culture-deprecating humor.

Arriving at the online gallery, Public Access Memories, we find ourselves looking at the desktop of a home computer whose wallpaper is a picture of a desk on which sits a worn, softcover book titled Home Offices. Visitors select an emoji avatar. Other emojis may be floating about; these are other gallery-goers. As we mouse around the screen, images–a daisy, a pen, a yellow, rubber glove–appear and disappear under the cursor. We enter the exhibition at the bottom right corner and move through each image/installation this way like turning pages of a virtual book.

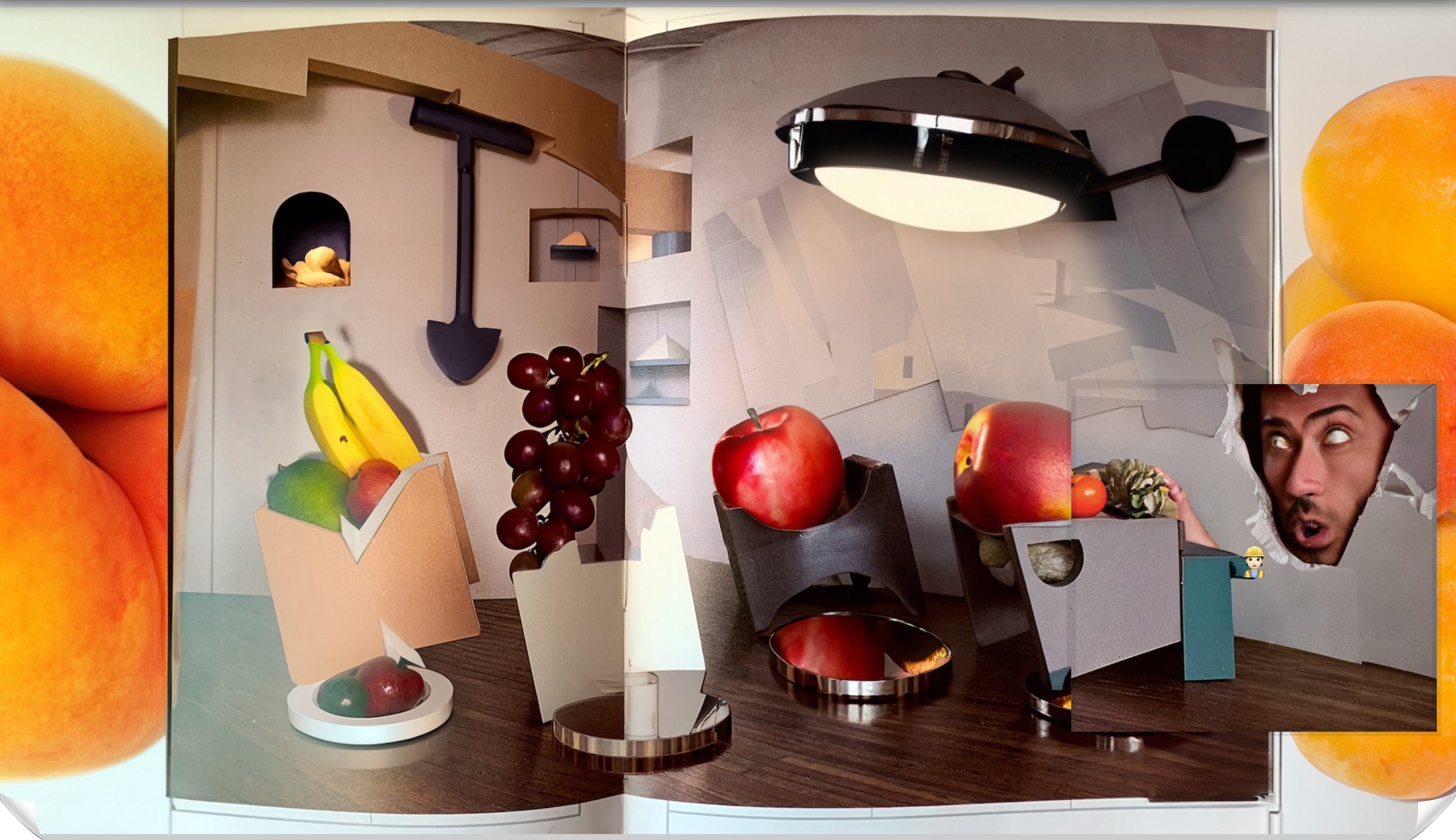

The works in HomeOffices are based on images from a 1984 look book of office furniture. The originating interiors dense and airless, dated and bizarre. Making the strange stranger, the artist added objects–some human or animal–to the scenes using AI. The image viewers encounter when they click into each space, is the final iteration of the collage. They can explore the images, which flicker and change revealing random-looking objects, which are the AI suggestions the artist dismissed. If you mouse over the globe on the desk, it becomes a basketball, then a cluster of balloons.

This haunted history of rejected versions is one of many ways the work is deeply layered. Avatars proceed though virtual rooms that can be understand as collages or spatially as virtual installations. An avatar, representing a whole person, moves through the space suggesting they are installations, but a binding seam passes vertically though some images, implying the rooms are two dimensional and we are looking in a book. Occasional objects appear to be placed on top of a page further confusing our viewpoint. Meanwhile, viewers access the exhibition from computers, most likely in their home space, possibly at a desk. This is the reality parfait the work creates, layering the viewer into its gaudy claustrophobia. In the unlikely event that a viewer feels underwhelmed, each installation-collage hosts an AI generated soundtrack related to the objects in the room and occasional pop-ups vie for our attention.

The pandemic hastened our adoption of communication technologies and drove our work lives into all hours of the day in some Philadelphia Experiment-type, mutated collapse of time and space. Humans hardly have the time to ask essential questions like, what are we working for? And, Can we mute the discomfort by redecorating our offices? The playfulness and humor in HomeOffices, consistent with the artist’s larger body of work, is funny-dark. The nightmare-like deformities, vagueness, and misinterpretations of AI not only generate appropriate imagery, but provide an apt metaphor of the zeitgeist. Is artificial intelligence cool or scary? Will it help or hurt us? Art is the sometimes-uncomfortable mirror of how we are living and what we value. Is working from home working for us? Greber’s HomeOffices does not answer these questions, but it suggests the call is coming from inside the house.

Written by Emily Farranto

A Well-Lighted Place: Public Access Memories (PAM)

“…Each night I am reluctant to close up because there may be some one who needs the café.”

“Hombre, there are bodegas open all night long.”

“You do not understand. This is a clean and pleasant café...”

This is part of a conversation between two waiters in Ernest Hemingway’s short story “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place.” The older waiter suggests that people need places where they can see other people in a warm, welcoming environment. Digital artists (artists who use code, the internet, or computers as a medium) may create in dark-mode and dwell in proverbial basements, but their work and community needs places to exchange and congregate. Digital art has not been entirely left out of the museums and galleries that comprise “the art world,” but these spaces do not necessarily meet the needs of digital art. On the contrary, digital artists have had to conform to the physical settings when a virtual space is the intended one.

Artwork that engages with the internet potentially loses something significant when it is contextualized in traditional art spaces. Artist Jenna deBoisblanc created Public Access Memories (PAM) to provide a place where digital art and internet art can be seen as intended, mostly from home, while enjoying contextualizing and community-building aspects of a physical gallery. PAM, like the café in the story, provides net artists a space to connect with viewers.

You are bodiless when you arrive at PAM. Choosing an avatar from a bank of emojis allows visitors to be embodied. You see other gallery-goers in the form of emojis floating about the space. When the gallery is closed, as it is between exhibitions, you land on an image of a desktop, the familiar display of icons on a home computer and, for Dave Greber’s solo exhibition, an image of a wooden desktop on which a book, Home Office (the exhibition title) sits. Your avatar can retrieve a glass of virtual wine from a table before moving through the exhibition.

Prehistoric humans made art on cave walls. To this day, viewers stand where those artists stood in the dark. This ancient impulse to make art had nothing to do with a gallery system. Then agriculture happened, and private property, and eventually those with wealth and power filled their rooms with art, which had become a symbol of privilege. When palaces could no longer hold royal collections, outbuildings were built, the first galleries and museums. Academies formed, and they also became arbiters of taste and value in Western art. In the late nineteenth century, artists and dealers began to self-emancipate and form commercial galleries around the showing and selling of art, for the most part, paintings and drawings.

Digital artists have been making and sharing their work since computer art arrived in the 1950s or 60s depending on who you ask. Like cave art, digital art was made from the impulse to create, using newly available technology rather than pigments or stone. Digital art has been shown in art museums and galleries, but the inescapable fact is that these spaces were developed to house and exhibit objects. This is the context into which digital art has tried to fit in.

The white cube model of a gallery provides not only space, but context, signifying that what’s inside its walls holds meaning beyond its raw material, beyond its face value. In the expanse of the internet, digital artists need spaces to show their work, and to connect and belong. PAM provides a welcoming, well-lighted space.