The Body Electric

Dave Greber & Sophia Belkin’s "Glimmerloom" by Tommy Doyle

John Bernhardt Smith, an American professor of entomology, is credited with having developed the glass lidded box that many are familiar with today as the preferred way to display insect collections. He developed the standardization of such boxes with his father, a cabinet maker, during his time as assistant curator of insects at the National Museum of Natural History (known then as the National Museum of Washington). They are still known as Schmidt or Schmitt boxes, as Smith had adopted the anglicized version of his family name.

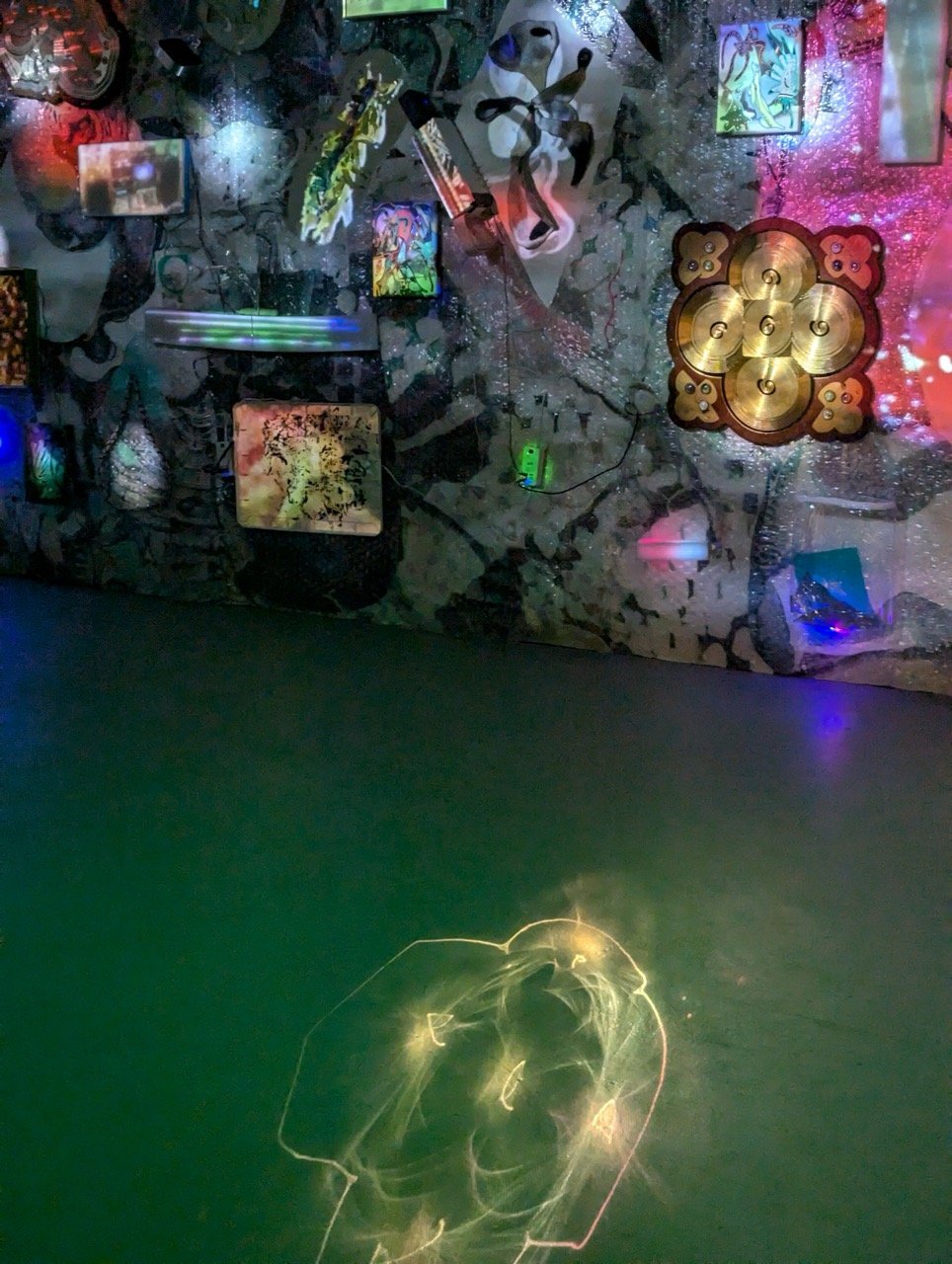

The work Glimmerloom by Dave Greber and Sophia Belkin first appears similar to a Schmidt/Schmitt box; a collection of three-dimensional, creature-like shapes laid flat on a two-dimensional service. However, the work defiantly escapes comparison by presenting itself moving, fluid, and alive. Unlike an entomologist’s collection or a Renaissance “cabinet of curiosities” or “wonder room” (Kunstkammer, Wunderkammer), Glimmerloom contains no boundaries or barriers that seek to categorize, chronicle, or define objects within a boundary. The sculptural elements are instead more like growths that emerge from a swirling painted backdrop. It’s an anti-cabinet; a collection that was never intended to be owned; John Carpenter’s 1982 film “The Thing”, an alien matter that is foreign, but also in us.

Wunderkammer without borders

There is a practice in entomology that requires a “killing jar” to kill a captured insect with minimal damage, but the Glimmerloom contains no reference to death, capture, or stillness. It’s all sustaining, none asking for alive. It doesn’t emulate the type of oddities popularized by retail stores like San Francisco’s Paxton’s Gate (or Baltimore’s own, Bazaar) that harken to the Victorian obsession with dying. The tension that that makes Glimmerloom a robust experience over a visual replica of a cabinet of curiosities or Schmitt/Schmidt box is that the things that are pinned down are not restricted by their placement, they move with the aid of projections and motors and wind, they’re kinetic, as much machine as they are biological. They didn’t die in order to be presented, they in fact seem to not just live, but thrive as their wings are pinned to a surface.

The German entomologist Maria Sybilla Merian was born in 1646 to a father who was an engraver and publisher and encouraged in childhood to paint and draw by a stepfather who was a flower and still life painter. She gained access to the gardens of wealthy citizens through work as a drawing instructor for their children and documented and collected insects during this time. By somewhat masquerading as as naturalist painter and illustrator, she was able to document the lifecycles of butterflies and the development of frogs, which produced detailed studies that dispelled the idea of spontaneous generation, the belief that insects were “born of mud” and furthermore deemed “beasts of the devil”. The starkness and frankness present in Merian’s work is not anything akin to what is presented by Belkin and Greber, but there is a similarity in the decorative flourishes, exaggerated forms, and fiction that exists in creating both abstraction and cramming all lifecycles of a single animal into a single image. Merian too may have not actually observed with her own eyes some of the things that she was “documenting”, which is its own type of “science fiction”.

The Killing Jar

The wedding of the machine to the organic is poignant now for the explosion of artificial intelligence, which actually is a tool utilized by Greber and Belkin (and especially in Greber’s own individual practice). There’s a historical tendency for creatives to imagine what this looks like in a gothic/steampunk fashion, human inventiveness and science bringing the capability to reanimate (think Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein”, Yorgos Lanthimos “Poor Things”) or in a science fiction style, skewing dystopian of course (“Do Robots Dream of Electric Sheep” and it’s descendent “Blade Runner” or “Terminator”). However, dystopia and horror are the antithesis of the Glimmerloom. For all of their uneasiness and uncanny movements, they breathe and glow with a vibrancy and pastel-like calmness. The robots aren’t taking over, the monster isn’t coming to your village - it sits before you, happy to exist, minding its own business. It inspires a specific type of affection, like observing a bird from a window as you work on a laptop, or hearing the rhythmic snoring of a dog that sits before a television. Existing with nature and technology side by side is an essential part of the contemporary human experience and it behooves us, it’s imperative, that we work to find the perfect balance there.

An anti-collection

Another essential part of being alive is making meaning of it all, finding reason and rationale from things that are purely natural. It’s why we have myths and religion. The Victorian obsession with death that inspired the collection of post-mortem photos, death masks, and memento mori was a way to make tangible the realities of the high mortality rate. But collections, knowledge, and understanding, new or old, are noble and necessary but ultimately futile. We burned the Library of Alexandria but the waves of the Mediterranean continued to lap at its ruins, whether or not we knew the reason for the wind and storms that caused them. Glimmerloom, as an anti-collection in an anti-cabinet, doesn’t help us to categorize what we know or put definitions and borders around things. It isn’t an invitation to understanding because it isn’t inviting us to do anything at all; it just wants to be. And while viewing it can inspire a series of thoughts and ponderings, it sighs and wriggles and floats like plankton regardless of whether or not we inhabit its space. Live and let live.

A Specific Type of Affection

We take our phones into the wilderness with us. After all, isn’t technology an extension of being human, divine, and perfect as conceived by the/a God(s)? Scientific and technological advances are byproducts of our natural will to live, survive, and thrive. Furthermore, explorations into the possibility of interplanetary travel were partially inspired by H.G. Wells, Jules Verne, and Russian Cosmism. There’s a very human innate desire to extend ourselves infinitely in all directions, and that desire inspires works of creative fiction and “real” scientific inquiry all at once. For all of our efforts, science is a mythology; it’s an interpretation of what is laid before us, what glimmers in the loom, a tapestry in progress. It’s as much transcendental as it is “Twilight Zone”. “I Sing the Body Electric”; so do you.

Glimmerloom Runs September 6 - October 11, 2024 at Current Space

Glimmerloom

Dave Greber and Sophia Belkin

September 6 – October 11, 2024

Current Space, Baltimore, MD

Supported by a Professional Development Grant for adjunct faculty from the Center for Innovation, Research, and Creativity in the Arts (CIRCA) at UMBC.

This piece was projected onto the bubble-wrap screen